La Doria Spa v Global Resourcing Pty Limited [2012] NSWSC  144 (1 March 2012)

144 (1 March 2012)

Last Updated: 5 March 2012

| Case Title: | La Doria Spa v Global Resourcing Pty Limited |

| Medium Neutral Citation: | [2012] NSWSC 144 |

| Hearing Date(s): | 15 February 2012 |

| Decision Date: | 01 March 2012 |

| Jurisdiction: | Common Law |

| Before: | Harrison AsJ |

| Decision: | (1) The second defendant's notice of motion filed 2 September 2011 is dismissed. (2) Mr Ho is to answer interrogatories 28 and 29 within 14 days. (3) Access to the plaintiff to the email dated 6 October 2009 from Foo Wong to Steven Agosta is refused. (4) Costs are reserved. |

| Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - interrogatories - whether email is privileged - whether further discovery required |

| Legislation Cited: | Evidence Act 1995 Fair Trading Act 1987 (NSW) Trade Practices Act 1974 (Commonwealth) Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 |

| Cases Cited: | Beechman Group Ltd v Bristol-Myers Co [1979] VR 273 Boyle v Downs [1979] 1 NSWLR 192 British Assn of Glass Bottle Manufacturers Ltd v Nettleford [1912] AC 709 Chong v Nguyen [2005] NSWSC 588 Griebart v Morris [1920] 1 KB 659 Mulley v Manifold [1959] HCA 23; (1959) 103 CLR 341 Pratt Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation[2004] FCAFC 122; (2004) 207 ALR 217 Pratten v Pratten [2005] QCA 213 Preston v Star city Pty Ltd [2007] NSWSC 293 Schutt v Queenan & Anor [2000] NSWCA 341 The Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission[2002] HCA 49; (2002) 213 CLR 543 Yamazaki v Mustaca [1999] NSWSC 1083 |

| Texts Cited: | |

| Category: | Procedural and other rulings |

| Parties: | La Doria Spa (Plaintiff) Global Resourcing Pty Limited ACN 069 228 879 (First Defendant) (no longer an active Defendant) Lawrence Ho (Second Defendant) |

| Representation | |

| - Counsel: | R Francois (Plaintiff) C Freeman with Y Guo (Second Defendant) |

| - Solicitors: | Clayton Utz (Plaintiff) Leonard Legal (Second Defendant) |

| File number(s): | 2009/293592 |

| Publication Restriction: | |

- HER HONOUR: There are two further interlocutory motions before this court for determination. By notice of motion filed 2 September 2011, the second defendant seeks firstly, an order pursuant to Rule 21.2 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 ("UCPR") that the plaintiff provide discovery of the documents within the classes identified in the Schedule; and secondly, an order that the time for the second defendant to serve his evidence be extended to thirty (30) days after the plaintiff has provided discovery. If further discovery is granted, the plaintiff does not oppose the extension of 30 days for the second defendant to serve his evidence.

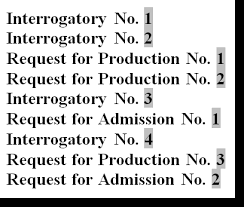

- By amended notice of motion filed 10 November 2011, the plaintiff seeks firstly, an order pursuant to UCPR 21.1 that the plaintiff have leave within seven days of the date of this order to file and serve interrogatories in the form attached to the letter dated 8 September 2011 from the plaintiff's solicitors to the second defendant's solicitors; secondly, that by 4.00 pm on 13 October 2011 (now past) the second defendant file and serve on the plaintiff answers to the interrogatories served pursuant to order one; and thirdly, pursuant to UCPR 33.8 the plaintiff be permitted to inspect and take a photocopy of the email dated 6 October 2009 from Foo Wong to Steven Agosta (the email) referred to in paragraph 13 of the affidavit of Steven Peter Agosta sworn 20 October 2011.

- There are three topics to be covered in this judgment, interrogatories, whether the email is the subject of legal professional privilege, and finally, whether there should be further discovery. I shall deal with these topics in order.

- The plaintiff is La Doria Spa ("La Doria"). The first defendant is Global Resourcing Pty Ltd (In Liquidation) ("Global Resourcing"). In July 2011, Global Resourcing was placed into liquidation. The plaintiff has not sought leave to proceed against the first defendant. The second defendant is Lawrence Ho ("Mr Ho").

- In January 2009 La Doria commenced these proceedings against Global Resourcing by statement of claim in Victoria seeking to recover €1,333,408.60 for goods sold and delivered. In March 2009 the Supreme Court of Victoria transferred these proceedings to this court.

- On 30 July 201 0, Barr AJ granted leave to La Doria to file an amended statement of claim joining Mr Ho as the second defendant. Mr Ho was employed by Global Resourcing as its contract trading business consultant. He was not a director of Global Resourcing. Parts of the pleadings have been summarised by Bar AJ. I gratefully acknowledge that I have reproduced some parts of his Honours judgment.

- The plaintiff is La Doria Spa, a company incorporated in Italy and listed on the Italian Stock Exchange. La Doria is in the business of manufacturing and supplying canned foods, such as peas, tomatoes, baked beans and spaghetti. La Doria's goods are sold to buyers in many countries around the world, including for Woolworths and Coles supermarkets in Australia. Global Resourcing Pty Ltd is incorporated in Australia and at all material times carried on business in New South Wales.

- La Doria claimed that pursuant to a number of contracts it sold and delivered to Global Resourcing quantities of goods in 2007 and 2008 but that it had not been paid or fully paid for them.

- Quantities of goods contracted for, rates and calculated totals have been particularised. La Doria asserted that each of the contracts was formed by the exchange of a series of email messages. The precise meaning of those messages is to some extent obscure and needs explanation and evidence will be adduced of the meaning of terminology used by the parties during the course of that correspondence.

- The six contracts may be summarised as follows:

(1) Pea Agreement: made about May 2008 for canned peas;

(2) The first budget agreement: made about September 2007 for canned beans and pasta;

(3) The second budget agreement: made about August or September 2007 for canned tomatoes;

(4) The first home brand agreement: made about March 2007 for canned tomatoes, beans and pasta;

(5) The second home brand agreement: made about February 2008 for canned beans and pasta;

(6) The third home brand agreement: made about September 2007 for canned tomatoes.

- In Global Resourcing's original defence (filed 2/9/09), it asserted that the unit rates put forward by La Doria did not apply. Instead, other rates applied. Those rates were not universally lower than the ones relied on by La Doria, but were mostly lower and the total amount that they produced as owing for each of the contracts was lower. The unit rates were orally agreed upon by telephone between one Cesare Concilio on behalf of La Doria and Lawrence Ho on behalf of Global Resourcing. As Barr AJ stated, an unattractive defence emerged, it being that any proposal and acceptance of unit rates in the exchanges of emails was of no effect because the parties were already bound to apply such rates as Mr Concilio and Mr Ho had agreed. La Doria has maintained its claim of breaches of the written contracts (by chain of emails) against Global Resourcing (in liquidation) but has not sought leave to proceed against it.

- The way in which the first home brand agreement is dealt with will exemplify them all. As provided in the Further Amended Statement of Claim ("FASC") filed 21 June 2011

First Home Brand Agreement

20. By an agreement made in or about 2007 between the plaintiff and the first defendant, and in accordance with the Agreed Structure, the plaintiff agreed to sell and the first defendant agreed to buy canned beans and pasta ("First home Brand Goods") for delivery to the first defendant or at the first defendant's direction ("First Home Brand Agreement').

Particulars

(a) The First Home Brand Agreement is partly written and partly to be implied.

(b) in so far as it is written, the First Home Brand Agreement is comprised of and/or evidenced by the following documents:

(i) an email chain ending 26 March 2007 between the plaintiff and first defendant, an email chain ending 13 April 2007 between the plaintiff and first defendant and the chain of emails between the plaintiff and the first defendant ending on the dates referred to in the rows numbers 94 to 258 in Schedule A to this Statement of Claim; ("First Home Brand Emails);

(ii) order confirmation numbered 3208 and 3209 ("First home Brand Orders");

(iii) the invoices referred to in the rows numbered 94 to 258 in Schedule A to this Statement of Claim, each of which stated a date for payment 45 or 60 days from the date of the invoice ("First Home Brand Invoices"); and

(iv) the non-negotiable bills of lading referred to in the rows numbered 94 to 258 in Schedule A to this Statement of Claim ("First Home Brand Bills of Lading").

(c) In so far as it is to be implied, the First Home Brand Agreement is to be implied:

(i) from a course of dealings between the plaintiff and the first defendant whereby the plaintiff issued invoices to the first defendant payable either 45 or 60 days from the date of such invoices;

(ii) as it is necessary for the reasonable or effective operation of the agreement in the circumstances of the case; and/or

(iii) as it is reasonable and equitable, necessary to give business efficacy to the agreement, it is obvious, capable of clear expression and does not contradict any express term of the agreement.

21. There were terms of the First Home Brand Agreement that:

(a) the plaintiff would deliver to the first defendant (in the manner prescribed by the First Home Brand Agreement):

(i) 114,800 trays of canned beans with each tray containing twelve 425 ml cans at a price of E2.30 per tray; and

(ii) 108,000 trays of canned spaghetti with each tray containing twelve 425 ml cans at a price of E2.90 per tray;

(First Home Brand Orders and First Home Brand Invoices)

(b) The first defendant would pay the plaintiff for each shipment of First Home Brand Goods in the sum appearing on the corresponding invoice, by the time for payment appearing on such invoice, such time being a reasonable time after the date of the invoice (First Home Brand Invoices and particular (c) subjoined to paragraph 20 above);

(c) The plaintiff would deliver the First Home Brand Goods to the defendant on a "F.O.B." basis namely, free on board, meaning that the plaintiff would satisfy its obligation to deliver the First Home Brand Goods to the first defendant by delivering them to a carrier nominated by the first defendant at the Port of Naples or the Port of Salerno (First Home Brand Orders, First Home Brand Emails and First Home Brand Bills of Lading); and

(d) Commission was payable to FTC by the plaintiff in respect of the goods referred to in paragraphs 21 (a)(i) to (ii) (First Home Brand Emails).

22. In pursuance of the First Home Brand Agreement between November 2007 and July 2008, the plaintiff duly delivered the First Home Brand Goods the subject of the First Home Brand Invoices to the Port of Naples and the Port of Salerno to the carriers nominated by the first defendant together with the First Home Brand Invoices.

23. In the premises, the first defendant became liable to pay the plaintiff for the price of the First Home Brand Goods the subject of the First Home Brand Agreement being E1,443,212.30

24. The first defendant has refused, failed or neglected to pay this amount in full to the plaintiff and is indebted to the plaintiff in the sum of E210,292.45 in respect of the first Home Brand Invoices which is due and payable.

- The FASC then details the claims against Mr Ho as follows:

First Home Brand Representations

66. Further between September 2007 and 2 September 2009 the first defendant and Ho represented to the plaintiff that the first defendant would pay the prices set out in paragraph 21(a) above for the First Home Brand Goods as invoiced from time to time (i.e. the First Home Brand Invoices) (" First Home Brand Representations ").

Particulars

(a) The plaintiff will rely upon the conduct of the defendants, namely the fact that the first defendant and Ho received from the plaintiff the First Home Brand Orders, the First Home Brand Invoices and the First Home Brand Bills of Lading which were consistent with the First Home Brand Representations and did not assert that those matters were incorrect.

(b) The plaintiff will rely upon matters referred to in paragraph 22 above and the fact that until the defence in this proceeding dated 2 September 2009 neither the defendant nor Ho contended that the proper price was anything other than that appearing in the First Home Brand Orders, the First Home Brand Invoices and the First Home Brand Bills of Lading.

(c) In the circumstances it was reasonable to expect that the first defendant and Ho would disclose to the plaintiff that the first defendant did not intend to pay the price appearing in the First Home Brand Orders and the First Home Brand Invoices.

(d) Such silence or omission to disclose to the plaintiff by the first defendant and Ho was misleading and deceptive and / or likely to mislead or deceive.

67. Acting in reliance on the truth and accuracy of the First Budget Representations, the Second Budget Representations, the Second Home Brand Representations (as defined in paragraph 75 below), the Third Home Brand Representations (as defined in paragraph 84 below) and the First Home Brand Representations and induced thereby, the plaintiff entered into and performed, and continued to perform the First Home Brand Agreement.

68. To the knowledge of Ho the First Home Brand Representations were untrue, false, misleading and deceptive and/or likely to mislead or deceive in that, unknown to the plaintiff, the first defendant did not intend to pay the First Home Brand Invoices and in particular in or about March to May 2006 Concilio and Ho had a telephone conversation the substance of which was:

(a) that the price which the first defendant would pay to the plaintiff for goods the subject of the First Home Brand Agreement would be:

(i) E1.955 instead of E2.30; and

(ii) E2.50 instead of E2.90.

(b) that such amounts referred to in 68(a) above would not be paid to the plaintiff by the first defendant unless and until the plaintiff submitted invoices to the first defendant for those amounts.

Particulars

See paragraphs 25(b) and 26 of the Defence and 34 to 39 of the Leonard Legal Letter.

69. In so far as the First Home Brand Representations were with respect to future matters, the first defendant and Ho did not have reasonable grounds for making those representations.

70. In the premises the making of the First Home Brand Representations constituted conduct by the first defendant in trade and commerce in breach of s 52 of the TPA (" Global TPA First Home Brand Breaches ").

71. Further, in the premises and by reason of the matters set out in paragraphs 66 and 68 and the particulars subjoined thereto, Ho:

(a) aided, abetted, counselled and procured; and

(b) was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in and party to the Global TPA First Home Brand breaches within the meaning of s 75B of the TPA (" Ho's TPA First Home Brand Breaches ").

72. Further, in the premises the making of the First Home Brand Representations constituted conduct by the first defendant and Ho in trade and commerce in breach of s 42 of the FTA (" FTA First Home Brand Breaches ").

73. Further, the First Home Brand Representations were made by Ho:

(a) knowing that the representations were false;

(b) without believing that the representations were true; and/or

(c) recklessly careless as to whether the representations were true.

( " Ho's First Home Brand Deceit " )

74. By reason of the:

(a) Global TPA First Home Brand Breaches;

(b) Ho's First Home Brand TPA Breaches;

(c) FTA First Home Brand Breaches; and

(d) Ho's First Home Brand Deceit;

(i) the plaintiff has suffered loss and damage;

and

(ii) the first defendant has made profits.

- The reference in the particulars under para 68 to the Leonard Legal Letter is to the letter supplying particulars to which I have referred. TPA means theTrade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) and FTA means the Fair Trading Act 1987.

- The case against Mr Ho concludes as follows:

Breach of fiduciary duties

93. By reason of the conduct of Concilio referred to in [paragraph] ... 68 ... Concilio acted in breach of Concilio's Fiduciary Duties in that he;

(a) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties in good faith and in the best interests of the plaintiff;

(b) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties for proper purposes;

(c) failed to act honestly at all times in the exercise of any power and the discharge of any duties;

(d) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person in a like position and with like responsibilities would exercise in the circumstances; and

(e) improperly used the position as an employee of the plaintiff to cause detriment to the plaintiff.

Concilio's Breaches of Duty

94. Concilio was not authorised by the plaintiff to engage in the conduct alleged in [paragraph] ... 68 ... and the plaintiff was unaware of the occurrence of that conduct.

95. At all times Ho and thereby the first defendant were aware;

(a) of Concilio's breaches of duty; and

(b) that La Doria was not aware of Concilio's breaches of duty.

Particulars

(a) The plaintiff refers to and repeats paragraphs 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 39, 41, 48, 50, 57, 59, 66, 68, 75, 77, 84 and 86 above and the particulars of those paragraphs.

(b) The particulars in (a) are the best particulars the plaintiff is at present able to provide.

(c) The plaintiff reserves the right to provide and rely on further particulars of any further matters which arise at trial.

96. Further, in the premises the first defendant;

(a) benefited from,

and Ho and the first defendant:

(b) aided, abetted, counselled or procured;

(c) induced;

(d) knowingly participated in; or

(e) were knowingly concerned in,

Concilio's Breaches of Duty.

Particulars

(a) The plaintiff refers to and repeats paragraphs 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 39, 41, 48, 50, 57, 59, 66, 68, 75, 77, 84 and 86 above and the particulars of those paragraphs.

(b) The particulars in (a) are the best particulars the plaintiff is at present able to provide.

(c) The plaintiff reserves the right to provide and rely on further particulars of any further matters which arise at trial.

97. In the premises Ho and the first defendant;

(a) received and hold on constructive trust for the plaintiff any benefit derived from Concilio's breaches of duty; and

(b) are liable to compensate the plaintiff for any loss and damage suffered by it as a consequence of Concilio's breaches of duty.

- In Mr Ho's defence filed 22 June 2011, he denies the representations. He says that he did not receive or read the orders, invoices or bills of lading. Mr Ho also denies that he made the representations.

Interrogatories

- The first point that counsel for Mr Ho made is that La Doria cannot succeed on both the contract claims and the misrepresentation claims, as they are claims in the alternative. If La Doria succeeded on the contact claim (ie, it entered into the agreements at the prices it alleges), then it could not establish the misrepresentations and vice versa. Global Resourcing is in liquidation and the contract claims are not defended by it. Mr Ho does not plead to the contract claims.

- Counsel for Mr Ho referred to a portion of the transcript before Barr AJ on 28 July 2010 .

"FRANCOIS: Your Honour, may I just orally open then, which is this, the case concerns a claim by an Italian company who entered into agreements with an Australian company for the export and in Australia the import of canned goods of various kinds. So the Italian company sells the goods to the Australian company which imports them and sells them on to places like Woolworths.

The Italian company says it had contracts with the Australian company, that were written, and certain prices were agreed for the products that were supplied. That's the claim as pleaded.

The defence says, as far as we understand it. While you might have written agreements, there was an earlier oral conversation between the defendant's employee and the plaintiff's employee where they agreed on different prices and those prices were to prevail in the face of the later negotiations.

The proposed amendments seek to deal with that allegation. So the proposed amendments seek to deal with an allegation that an otherwise written agreement is superseded and somehow overwritten by an earlier agreement reached between two people who negotiated the written agreement. Should that prove to be correct and my client cannot recover the written agreed price but must pay the lower earlier agreed price, my client wishes to plead claims that it did not know about that and that it was misled by the conduct of its employee and of the defendant and its employee ." [emphasis added]

- Leave was granted to join Mr Ho as second defendant. Leave was also granted to file an ASC rasing both the contract claims and in the alternate misrepresentation claims against Mr Ho. Barr AJ did not consider that both claims could not be pleaded in the ASC. While it is likely that at trial La Doria can only succeed on either the contractual claims or the misrepresentation claim it is possible that the court may find some of the contracts were written and other were made orally by Mr Ho and Mr Concilio that may give rise to the false and misleading claim. Hence, I do not agree with Mr Ho's submission that only one claim can be maintained.

- Counsel for Mr Ho stated in open court that Mr Ho would not give evidence at trial except so far is necessary to support assumptions and/or facts relied upon by his expert, Mr Ross. If further evidence is to be relied upon by either party, Mr Ho will review his position. Mr Ho had been referred to in earlier Victorian proceedings as Lauren Ho. Counsel for Mr Ho also stated in open court that Lauren Ho and Lawrence Ho are one and the same person. In the light of this statement, the interrogatories that address this identity issue of Mr Ho are no longer necessary.

- Counsel for La Doria submitted that because of the stance taken by Mr Ho, (not to give evidence) in order for La Doria to prove its case, the answers to these interrogatories are necessary.

The law

- Rule 22.1(4) of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules reads:

"In any case, such an order is not to be made unless the court is satisfied that the order is necessary at the time it is made."

- The accepted test of necessity is what is reasonably necessary for the disposing fairly of the matter or necessary in the interests of a fair trial: Boyle v Downs [1979] 1 NSWLR 192 at 205, Yamazaki v Mustaca [1999] NSWSC 1083. The answers which are sought are material in the sense that they may enable the plaintiff either to maintain its own case or to destroy the case put against it: Griebart v Morris [1920] 1 KB 659 at 664 and Schutt v Queenan & Anor [2000] NSWCA 341 at [12].

- In Chong v Nguyen [2005] NSWSC 588, Rothman J said at [16]:

"The word 'necessary' when used in relation to a requirement on the exercise of a power granted to a court should generally and does here mean 'reasonably required or legally ancillary' to the achievement of the goal, in this case, of a fair trial. I refer to the joint judgment of Gaudron, Gummow and Callinan JJ inPelechowski v Registrar, Court of Appeal [1999] HCA 19; (1999) 198 CLR 435 which, while determining whether there was a valid basis for contempt proceedings, examined the power of the District Court to issue injunctive relief. They said:

'The term "necessary" in such a setting as this is to be understood in the sense given it by Pollock CB in Attorney-General v Walker [1849] EngR 223; (1849) 3 Ex 242, namely as identifying a power to make orders which are reasonably required or legally ancillary to the accomplishment of the specific remedies for enforcement provided in Division 4 of Part 3 of the District Court Act. In this setting, the term "necessary" does not have the meaning of "essential"; rather it is to be "subjected to the touchstone of reasonableness" ( State Drug Crime Commission of NSW v Chapman (1987) 12 NSWLR 477 at 452).'"

- Interrogatories 1 to 27 ask questions of Mr Ho in relation to various emails passing between him and his counterpart in La Doria, Cesare Concilio and emails passing between some other employees of La Doria and Global Resourcing. They ask Mr Ho what oral conversations there were and whether certain emails were brought to his attention. They also ask Mr Ho's about his knowledge as to the content of emails sent between employees of La Doria to other employees in Global Resourcing.

- La Doria submitted that the answers to these interrogatories are necessary because, firstly, La Doria relies on Mr Ho's statements as recorded in that letter regarding his conversation with Mr Concilio as admissions to prove the allegations in paragraphs 41, 50, 59, 68, 77 and 86 of the FASC; secondly, subpoenas for the production of documents containing the instructions providing the basis for that letter have so far been unproductive; and thirdly, there is currently no other evidence available to prove those allegations. Mr Ho's knowledge and participation in the matters, that are the subject of the emails, bear upon his denial of the representations being made. Counsel for Mr Ho submitted that the questions that are asked in relation to these emails are not necessary as the plaintiff's solicitor can obtain evidence and answers to these questions from Mr Concilio and other employees of La Doria.

- So far as Mr Concilio is concerned, Barr AJ in his judgment dated 30 July 2010, recorded at [6] that Ms Francois, for La Doria, informed the Court that while Mr Concilio had been an employee of La Doria that was no longer the position and Mr Concilio, who resides in Italy, cannot be located. That was the situation as at July 2010. No evidence was provided by La Doria as to what steps, if any, have been taken since then to locate the crucial witness, Mr Concilio. It may be that he is unwilling to provide evidence as there is a claim pleaded against him in the further amended statement of claim but there is no evidence to this effect. There are other employees who have authorised the emails emanating from La Doria so enquiries can be made of them in relation to the matters that involve them. It is my view that without some evidence to show the steps to locate Mr Concilio since July 2010 and his unwillingness to give evidence, I cannot say that these interrogatories are necessary at this time.

- That leaves interrogatories 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, and 34 to 40.

- Interrogatories 28 to 30 ask:

28 Were you in any or all of 2006, 2007 and 2008 (stating which) responsible for managing the first defendant's trading relationship with the plaintiff and familiar with the plaintiff's business dealings insofar as they concerned the plaintiff?

29 If "no" to 28, when did you first:

(a) become responsible for managing the defendant's trading relationship with the plaintiff on behalf of the first defendant; and

(b) acquire knowledge of its business dealings with the plaintiff?

30 Were you in 2007 and 2008 kept informed of orders of product from the plaintiff?

- As it is Mr Ho's current position that he will not give evidence at trial, it is my view that these interrogatories (28 and 29) asking him when he was responsible for managing Global Resourcing's trading relationship with Le Doria are necessary. Interrogatory 30 is too vague and is therefore not necessary.

- Interrogatories 31 and 32 ask Mr Ho to confirm what was said by his counsel in court in Victoria and also whether paragraph 4 of his affidavit was true and correct. In the affidavit Mr Ho would have sworn the contents of the affidavit are true and correct. There is a transcript of what Mr Harrison of counsel said in court is available. It is my view that it is not necessary to go behind the transcript and the oath of Mr Ho. Hence, Mr Ho is not required to answer these interrogatories.

- On 15 April 2010, Mr Ho entered into a retainer with Leonard Legal in respect of these proceedings. Counsel for Mr Ho submitted that interrogatories 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and 40 specifically seek answers to confidential communications that were given after these proceedings had commenced and for Mr Ho to answer them would require him to waive his claim for legal professional privilege. Counsel for La Doria submitted that legal professional privilege does not cover instructions given by Mr Ho to answer La Doria's further and better particulars, or alternatively, that Global Resourcing waived privilege by disclosing the substance of the privileged communications in its defence dated 2 September 2009. The answers to particulars were given before Mr Ho was joined as a party to these proceedings; but if Mr Ho did give these instructions it would have been on behalf of Global Resourcing after legal proceedings has been commenced. The liquidator (letter dated 19/10/11) (Ex B) states that it wishes to maintain its claim for privilege and does not waive its claim for privilege in relation to the proposed interrogatories.

- Interrogatories 34 to 40 read:

34. Prior to or on about 9 October 2009, did you provide the information or any of it (specifying which information) set out in paragraphs 1 to 6, 12 to 17, 23 to 28, 34 to 39, 45 to 50 and 56 to 61 of the LL Letter ("Relevant paragraphs"):

(a) to Steven Agosta or any other person at Leonard Legal (identifying the person); or

(b) someone else (identifying the person), for the purpose of communicating it to Leonard Legal?

35. If 'yes" to 34(a), do the Relevant Paragraphs accurately reflect the information you provided?

36. Did you receive a draft of the LL Letter and if so from whom?

37. Did you approve the contents of the Relevant Paragraphs before the LL Letter was sent and if so to whom did you convey the approval?

38. When did you first:

(a) read; and

(b) receive,

a copy of the LL letter?

39. Are the matter set out in the Relevant Paragraphs true and correct?

40. If "no" to 39, in what respects is any matter set out in the Relevant Paragraphs not true or correct?

Confidential communications

- Sections 118, 119 and 131A of the Evidence Act 1995 read:

"118 Legal advice

Evidence is not to be adduced if, on objection by a client, the court finds that adducing the evidence would result in disclosure of:

(a) a confidential communication made between the client and a lawyer, or

(b) a confidential communication made between 2 or more lawyers acting for the client, or

(c) the contents of a confidential document (whether delivered or not) prepared by the client, lawyer or another person,

for the dominant purpose of the lawyer, or one or more of the lawyers, providing legal advice to the client.

119 Litigation

Evidence is not to be adduced if, on objection by a client, the court finds that adducing the evidence would result in disclosure of:

(a) a confidential communication between the client and another person, or between a lawyer acting for the client and another person, that was made, or

(b) the contents of a confidential document (whether delivered or not) that was prepared,

for the dominant purpose of the client being provided with professional legal services relating to an Australian or overseas proceeding (including the proceeding before the court), or an anticipated or pending Australian or overseas proceeding, in which the client is or may be, or was or might have been, a party.

- The term "client" is defined in s 117(1)(b) of the Evidence Act to include an employee or agent of the client, which includes both Mr Ho and Mr Foo Wong.

- Section 131A provides:

131A Application of Part to preliminary proceedings of courts

(1) If:

(a) a person is required by a disclosure requirement to give information, or to produce a document, which would result in the disclosure of a communication, a document or its contents or other information of a kind referred to in Division 1, 1A, 1C or 3, and

(b) the person objects to giving that information or providing that document,

the court must determine the objection by applying the provisions of this Part (other than sections 123 and 128) with any necessary modifications as if the objection to giving information or producing the document were an objection to the giving or adducing of evidence.

(2) In this section, disclosure requirement means a process or order of a court that requires the disclosure of information or a document and includes the following:

...

(d) interrogatories,

..."

- UCPR 1.9(3) and the definition of "privileged document" in the Dictionary to the UCPR apply the Evidence Act to the determination of interlocutory disputes concerning privilege.

- In Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2002] HCA 49; (2002) 213 CLR 543 ( at 552 ) the High Court held:

"It is now settled that legal professional privilege is a rule of substantive law which may be availed of by a person to resist the giving of information or the production of documents which would reveal communication between a client and his or her lawyer made for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining legal advice or the provision of legal services, including representation in legal proceedings."

- In Pratt Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2004] FCAFC 122; (2004) 207 ALR 217, Stone J indicated that the High Court's exposition of the rationale for legal professional privilege in Daniels was consistent with the appellants' submission that there is a single rationale in Australia for legal professional privilege. Stone J found that the rationale applies both to litigation privilege and legal advice privilege, although Her Honour did not accept that adopting a single rationale should lead to a refusal to distinguish between the categories.

- The plaintiff's counsel also referred to Pratten v Pratten [2005] QCA 213 at [27] to [31] and [79]. In Pratten , Ms Smith gave evidence that she told her solicitor to notify that the disputed chattels were there [at her property]. At [30] and [31] Jerrard JA discussed the application of the well known principles in relation to Ms Smith's evidence. His Honour stated:

[30] Ms Smith's evidence of having given those instructions to Mr Roderick was given by her both in evidence in chief and in cross-examination. She clearly did so to establish that she had done all she could to offer a return of the claimed property, and to imply that if the solicitor had not written as instructed, then that was not her fault but his. She implied the same about the apparent failure of the solicitor to act on her asserted instructions about her counterclaim, which only appeared in her pleadings. In those circumstances, there was an inconsistency between, on the one hand, her conduct in the witness box, and, on the other hand, maintaining confidentiality as to what she told her solicitor, which inconsistency affected a waiver of any legal professional privilege existing to protect disclosure by the solicitor of what she told him to do. In Mann v Carnell [1999] HCA 66; (1999) 201 CLR 1, the joint majority judgment of the High Court records at CLR 13 that:

"and maintenance of the confidentiality which effects a waiver of the privilege. Examples include disclosure by a client of the client's version of a communication with a lawyer, which entitles the lawyer to give his or her account of the communication ... "; and

"Disputes as to implied waiver usually arise from the need to decide whether particular conduct is inconsistent with the maintenance of the confidentiality which the privilege is intended to protect ... What brings about the waiver is the inconsistency, which the courts, where necessary informed by considerations of fairness, perceive, between the conduct of the client and maintenance of the confidentiality; not some overriding principle of fairness operating at large."

Their Honours went on at CLR 15:

Disclosure by a client of confidential legal advice received by the client, which may be for the purpose of explaining or justifying the client's actions, or for some other purpose, will waive privilege if such disclosure is inconsistent with the confidentiality which the privilege serves to protect. Depending upon the circumstances of the case, considerations of fairness may be relevant to a determination of whether there is such inconsistency.

[31] Here the issue is the instruction Ms Smith gave to the solicitor, not the advice the solicitor gave. She asserted specific instructions were given, and Mr Conrick was not seeking to learn what advice the solicitor gave her; only whether the instructions were given as claimed. Assuming legal professional privilege originally existed with respect to the issue of whether she had given the instructions, she waived it in the sense described in Mann v Carnell by her own inconsistent conduct in asserting that she had. Considerations of fairness required that that matter, important to her credit generally and in her defence to the claim in detinue, be tested by cross-examination of the solicitor. Mr Pratten's subpoena was too wide and was set aside, but Mr Roderick was legitimately called as a witness and could give admissible evidence.

And at [79] Muir JA stated:

[79] The primary judge rejected the submission and refused to permit the solicitor to be called to give evidence. His Honour erred. The giving of instructions by a client to the client's solicitor to act in a particular way or to communicate a matter to the other side of litigation would not normally be regarded as attracting legal professional privilege. It is not a communication for the purposes of giving or receiving legal advice. But even if such a communication were privileged, it is difficult to see why the respondent, having asserted that a particular instruction had been given, had not waived any privilege which may have existed in the fact of the instruction. Generally, similar considerations apply to the documents which the respondent alleged she had given her solicitor.

- From a perusal of the answers to the further and better particulars by Global Resourcing and assuming that Mr Ho was involved in answering at least some of them, legal advice was given by the solicitor acting for Global Resourcing. If Mr Ho provided information it was provided on Global Resourcing's behalf not his. These communications are confidential. I understand that La Doria now alleges that as a result of the pleading by Global Resourcing in its defence, it now alleges that Mr Ho was involved in making misrepresentations to La Doria. La Doria is attempting to obtain evidence of Mr Ho's alleged misrepresentations by seeking to go behind legal professional privilege.

- Mr Ho is now a separate defendant to Global Resourcing . It was Global Resourcing who alleged that Mr Ho and Mr Concilio entered into other agreements. Mr Ho has denied that he did so in his defence. Global Resourcing has amended its defence and has withdrawn these allegations. It is my view that for Mr Ho to answer these interrogatories would require Global Resourcing to waive its claim for legal professional privilege. It should not be required to do so.

- The result is that Mr Ho is required to answer interrogatories 28 and 29.

- Counsel for La Doria at [36] to [44] of her submissions in reply (emailed the night prior to this hearing) made submissions against the solicitors acting for Mr Ho. Due to their seriousness of these submissions and late notice they were by agreement of the parties not dealt with at this hearing.

Access to documents

- On 16 September 2011, the plaintiff filed a subpoena (Ex C) addressed to the liquidator of Global Resourcing seeking the following:

"Any document comprising, evidencing or recording a statement by or instructions from Lawrence Ho, whether oral or in writing, proving the basis for paragraphs 1 to 6, 12 to 17, 23 to 28, 34 to 39, 45 to 50 and 56 to 61 of the letter dated 9 October 2009 from Leonard Legal to Clayton Utz."

- Documents have been produced by the liquidator. La Doria seeks access to an email from Foo Wong an employee of Global Resourcing to its solicitor Steve Agosta dated 1 October 2009. The liquidator of Global Resourcing maintains the claim for privilege but did not seek to argue this issue. However, the liquidator neither consents nor opposes the orders of the court. In my view, La Doria is trying a different path to obtain information that is the subject of legal professional privilege. Access to these documents is not refused.

Further discovery

- Under Part 21 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 the Court has power to order a party to give discovery. UCPR 21.2(4) reads:

"(4) An order for discovery may not be made in respect of a document unless the document is relevant to a fact in issue."

- Hence, UCPR 21.2(4) limits an order for discovery to those documents that are "relevant to a fact in issue."

- In Mulley v Manifold [1959] HCA 23; (1959) 103 CLR 341, Menzies J referred to the broader proposition that document which fall within the "train of enquiry" ought to be discovered. Menzies J (at 345) stated:

"I now turn to the pleadings to determine what are the matters at issue between the parties, because discovery is a procedure directed towards obtaining a proper examination and determination of these issues - not towards assisting a party upon a fishing expedition. Only a document which relates in some way to a matter in issue is discoverable, but it is sufficient if it would, or would lead to, a train of inquiry which would, either advance a party's own case or damage that of his adversary."

- The broader proposition that documents which fall within the "train of enquiry" ought to be discovered.

- Also in Mulley v Manifold , it was stated that the general rule is that an affidavit of discovery is conclusive evidence of discovery required to be given. There are exceptions that have been recognised to this general rule. In Mulley v Manifold , Menzies J at 343 referred to British Association of Glass Bottle Manufacturers Ltd v Nettleford [1912] AC 709 stated:

"... it was established that insufficiency [of the affidavit of discovery] might appear not only from the documents that also from any other source that constituted an admission of the existence of a discoverable document."

- A court must have "reasonable grounds for being fairly certain that there were other relevant documents which ought to have been disclosed": seeNettleford at 714; Beechman Group Ltd v Bristol-Myers Co [1979] VR 273 at 276 and Preston v Star city Pty Ltd [2007] NSWSC 293 per Hoeben J at [12].

- The reason that Mr Ho seeks further discovery is because his expert, Mr Andrew Ross a qualified chartered accountant, has been asked to provide an expert's report on damage and has deposed that he needs these further documents to prepare his report.

- So far as the claim for damages is concerned, Mr Alberto Festa, who is the director of Administration and Finance of La Doria, has given precise evidence as to what he would have done if he had became aware that prices had been agreed with Global Resourcing for the goods which were other than those contained in La Doria's invoices. He would not have tolerated it. He would have sold the goods to Global Resourcing's customers directly if they had not already been shipped. It is his view La Doria would have had very good prospects of selling those goods directly to those customers for the prices, which had been agreed with Global Resourcing, or higher prices.

- So far as any goods he could not sell directly to Global Resourcing's customers, Mr Festa says La Doria could have sold those goods for similar prices to other customers in the United Kingdom, Italy, Northern Europe, Japan or elsewhere. Mr Festa says that in the case of such goods, based on his experience, La Doria would have sold the goods for prices within 10 percent (above or below) the prices for those goods.

- The documents referred to in categories 1, 3, 5 and 7 of the Schedule are no longer sought. In each category where documents are still sought the words "refer or relate to" were deleted. La Doria submitted that Mr Ho has not advanced reasonable grounds for believing that the documents in any category in the Schedule exist.

- On 8 August 2011, La Doria provided a spreadsheet said to be "analysing revenue for 2007 and 2008." On 9 September 2011, La Doria provided a further spreadsheet. La Doria says that it has already given discovery in that it analyses its revenue for each product so as to show the price at which it sold the product to each customer, the number of units sold and the total value; and breaks down its sales of each product by the country of the customer, being Australia, New Zealand, Germany, South Africa, South Korea and Denmark.

- Mr Ross (Aff 6/9/11 at [17] and [18]) stated that (a) he could not reconcile spreadsheets to financial statements; (b) he did not know what currency is used but it was reasonable to assume it was Euros; (c) the spreadsheet did not include all relevant products; (d) the size of the product could not be identified; (e) the data is one value per product per customer per years and therefore it cannot identify the range of prices per product; (f) there were difference prices to different customers; (g) there was no identification of shipping, insurance etc, so he did not know what prices included and (h) there were no terms of trade identified. Andrew Wescott, solicitors for La Doria, replied that the spreadsheets provided include detailed sales information for 2007 and 2008 for "each product sold to the first defendant and other customers" or "of the products the subject of this proceeding by reference to customer and country of the customer."

- Mr Ross (Aff 11/11/11 at [ 9 ]) further stated that he needed documentation, which identified sales to each customer for each year with separate details for each product including details for each size of product. He required:

- Total volume sold

- Total amount invoiced for product costs

- Total amount invoiced and/or incurred for each category of incidental costs (insurance, shipping etc)

- Range of prices at which the product was invoiced

- Amounts disputed or not paid

- The categories of documents sought in category 2 the Schedule are those documents that evidence the sale by La Doria of similar goods "for similar prices to other customers in the United Kingdom, Italy, Northern Europe, Japan or elsewhere" during the relevant period the relevant period being from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2009.

- La Doria submitted that an order for discovery of the documents in the Schedule would be oppressive and disproportionate because Mr Ho in his notice of motion defines the "Relevant Period" as 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2009 and "Similar Goods" is defined as the goods referred to in La Doria's FASC, including but not limited to canned peas, canned beans, canned pasta and canned tomatoes. La Doria has sales of € 406.6M in 2007, € 448.3M in 2008 and € 445.9M in 2009 and most if not all of the sales were of similar goods.

- Category 4 of the Schedule seeks documents that evidence the costs La Doria would have incurred to find and transact with n ew customers during the relevant period. But Mr Festa's claim is based on a hypothetical, namely what he would have done if he had known of the different price agreements but the fact is that he did not know of them. The evidence sought does not exist.

- Category 6 of the Schedule seeks documents that evidence sales by La Doria of similar goods to other customers, including but not limited to the prices and terms of trade, during the relevant period. This is similar to category 2 but seems to be wider in that it includes worldwide sales.

- Category 8 of the Schedule seeks documents that refer or relate to or evidence La Doria's total sale (by product) and its customer base during the relevant period.

- La Doria submitted that Global Resourcing has its total sales by product and customer for 2007 and 2008 for the products and that this category of documents is not relevant to any matter in issue. La Doria further submitted that an order for discovery of the documents in category 8 would be oppressive and disproportionate.

- Category 9 of the Schedule seeks documents that refer or relate to or evidence La Doria's competitive position in its markets (by product) during the relevant period.

- La Doria submitted that there is no evidence that it has any relevant documents in this category and that this category of documents is not relevant to any matter in issue.

- Category 11 of the Schedule seeks documents that refer or relate to or evidence La Doria's debt collection history in relation to all customers generally for the period of three years prior to the date of the alleged misrepresentations, as well as any specific alternative customers that the plaintiff says it would have sold the relevant products to.

- Its annual reports (already provided) contain details of its provisions for doubtful debts in the relevant years. La Doria says that there is no evidence that it has a "canned goods division" in respect of which it makes discrete provisions for doubtful debts or write-offs. Mr Ho seeks documents relating to "instances and occasions where the plaintiff had had price disputes in its canned goods division as well as how those disputes were resolved". La Doria says this category of documents is not relevant to any matter in issue.

- It is my view that the categories of documents sought go beyond the issues in dispute. Further, for La Doria to provide these documents, when the company has a yearly turnover from canned goods and pasta of over € 400M is oppressive.

- An order for further discovery is refused.

Mediation

- I understand that there was an earlier mediation when there was only one defendant, Global Resourcing. Global Resourcing is in liquidation and is no longer an active defendant. M r Ho is now the only defendant in these proceedings. He has not had the opportunity to mediate the dispute. In view of the escalating costs being expended in these interlocutory skirmishes and the future legal costs that will be incurred at the future trial, it is my view that it would be worthwhile for the parties to go to mediation. The parties were to seek instructions concerning mediation and advise this court of their attitude when this judgment is delivered.

The orders I make are:

(1) The second defendant's notice of motion filed 2 September 2011 is dismissed.

(2) Mr Ho is to answer interrogatories 28 and 29 within 14 days.

(3) Access to the plaintiff to the email dated 6 October 2009 from Foo Wong to Steven Agosta is refused.

(4) Costs are reserved.

**********